At the height of his career, disaster struck. Armand’s eyesight began to fail, and in the mid 1980s he could no longer read or drive. Already in 1978, his ophthalmologist and longtime friend, Dr. Larry Gerbens, had diagnosed him with “early geographic atrophy,” another term for macular degeneration. It was difficult to predict what the progression would be, but it soon became obvious that Armand was facing a darkening future due to macular degeneration. Betty cried when she shared the news with the children.

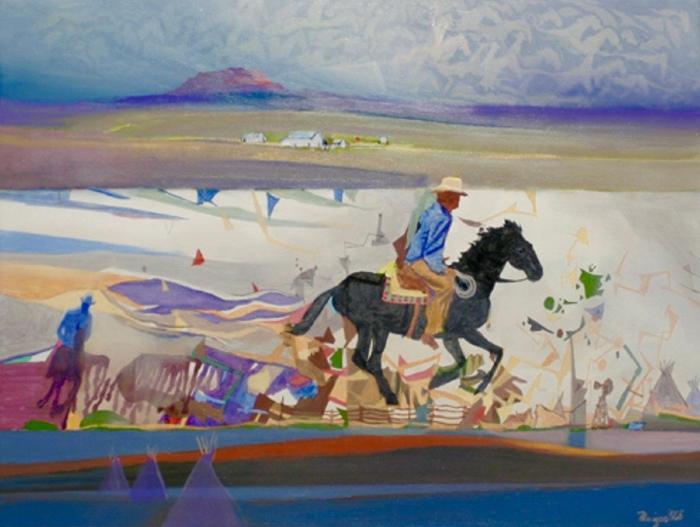

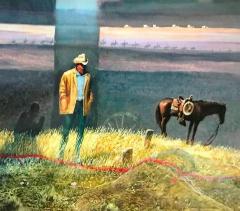

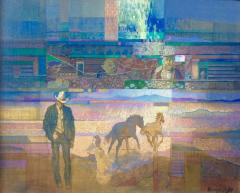

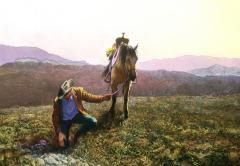

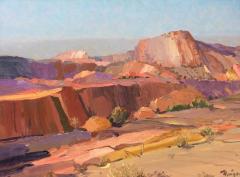

For an artist who uses his eyes for painting and for the details of painting, macular degeneration takes away your central vision. A person’s not blind in the sense that they can’t see, but their central vision’s gone. The colors have changed. The detail has changed.

Artist friend Carl Forslund said “his work is more ‘intellectual’ in that he is dealing with memories of impressions that he saw 30-40 years ago. He absorbed those and now he’s squeezing the sponge, so to speak, to get that out."

In Eye of the Artist, fellow ophthalmologists James G. Ravin and Michael F. Marmor give us a fuller understanding of this condition, and they focus on how various forms of eye disease altered the works of well-known artists such as Monet, El Greco, Cassatt, Degas, Munch, and O’Keeffe. Ravin and Marmor explain macular degeneration: “It not only affects visual acuity (that is, the resolution of small objects) but also diminishes the critical ability to judge contrast . . . . Even without a serious loss of acuity, many elderly individuals have difficulty recognizing objects at dusk or in dim light. Macular degeneration can also diminish color sense and make adaptation to changing light conditions more difficult.” The authors also mention that some artists, when their vision failed, turned to more tactile arts. Degas, for example, turned to sculpture; for O’Keefe it was pottery (Marmor & Ravin, The eye of the artist, 1997).

For his part, Merizon kept painting. Gerbens recalls: “In April of 1982, his vision had dropped, especially in his left eye, which was always worse than his right eye. He was at about 20/50 in his right eye, but he was already 20/200 in his left eye. So in four years there was a significant drop.” And there was no cure. “We did talk nutrition, because already then there were studies that showed good antioxidant therapy would not improve things but maybe would slow the progression down. And remember, his diagnosis was dry macular degeneration, where vision loss is usually gradual. Smoking cigars didn’t help deter it either. Words on the page look blurred. A darker empty area appears in the center of vision. Remember, the macula is that part of the retina that we use for our central vision. That’s the area that gives us our best acuity, as opposed to our peripheral vision. It’s also where the cones are. The cones give us color vision. The rods give us black and white” (Olson/Zandstra Interview, 10-22-12).

In a 2004 interview Betty commented: “After he had macular degeneration life did change for us. I had to stay home and drive him and take care of all the bills and more of the things at home that he would normally do. We had to become just very close because I had to be with him almost all the time. I also have to read to him. If there’s anything in the newspaper I try to scan the newspaper for him and read it to him every night” (Dornbush/Zandstra Interview, 6-21-04).

For over ten years Armand painted unrelentingly without further ophthalmological consultation anticipating he would soon be blind. “I know he didn’t see anybody in the meantime,” says Gerbens. “I lost Armand from 1982 to 1993. He was not seen for a decade.”

The changes were gradual, but they built up. Betty recalled, “[He] surprised us all. His work changed of course, gradually, and I think it became even more creative” (Dornbush/Zandstra Interview, 6-21-04).

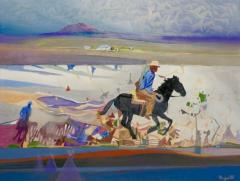

It was during this time Armand again took to marketing his own paintings, which by this time he was accustomed to doing. He went back to making the rounds to individuals such as Dr. Jack Chase. Chase recalls, “I started seeing Armand. He’d come in the office. You never knew what it was for until he walked in the door. We had a system. They’d buzz me and they’d say, ‘Armand Merizon’s here’. I’d say, ‘Well, why is he here? Is he sick or does he want to sell me a painting?’ Then they would tell me. If he wanted to sell me a painting I’d say, ‘Well have him come in the office.’ He never made an appointment. [laugh] He’d just come.

“He came to our house one evening to sell a painting. He’d pick the worst nights, a horribly, rainy, nasty night. The doorbell would ring. There he’d be. I’d think, ‘My gosh, what is he doing out here?’ It was sort of like Edgar Allan Poe. I remember my wife Donna saying, ‘Gosh, what is he doing out on a night like this?’

“He’d come over and if I didn’t want something I’d send him down the street a couple doors to Jim Bowman. Jim Bowman bought quite a bit of his art. I remember Armand came over one night and had a beautiful painting of a horse that I liked very much but Donna wasn’t too sold on it, so I sent him down to Jim Bowman and he bought it” (Merizon/VanHeest/Zandstra Interview of Jack Chase, 11-2-12).

This went on for several years, with difficulty.