Armand continued to experiment with new styles and techniques. Almost all waking hours were spent imagining and implementing these ideas in his studio, particularly so after he had been told the previous year he had an incurable eye disease.

As his paintings began to take their turn in recognized galleries and art magazines such as Art Gallery International, critics debated about how to categorize his work. Was Armand a realist, romantic, impressionist, modernist, abstract artist, or cubist? Chances are one will see all of these elements in his work, but he never aligned himself with any particular school. “I’ve done so much experimenting over the years that I’ll bend a technique to what I consider serving an end on a given painting,” he said, grinning. “I’m not what you call from any one school” (Dornbush/Zandstra Interview, 6-14-04).

When asked which one painting would highlight his career, Armand’s response was: “It’s hard to come to a standstill on one piece of work, and say, ‘this is it’, because I’ve been seeking, I want to know thoroughly the method and approach of what we call broadly ‘The Old Masters’. But at the same time, I’ve been wanting to apply this great technique, you might say chemistry, too, of materials that they had to start with, and master and manipulate one with the other. So, I feel thoroughly devoted and in reverence to the great traditionalists and at the same time I have remained restless, in search of something” (Zandstra Interview, 11-13-09).

Asked where his allegiance lay Armand replied, “Art is bigger than any country” (Merizon, The Psychology of Composition, 4-13-89).

According to his daughter, Michele, “He’s not been a part of any trend as far as I can tell. His art work comes from very deeply within him. It’s very genuine and it’s not any trend that he’s trying keep up with. He hasn’t been involved or sucked into any kind of art movement. It’s all been very him. And this work has been in him and it has had to come out. Regardless of finances, regardless of family, regardless of anything, his work is there and it was gonna come out the way he was meant to express it. Whether anybody liked his work was really not the point. The point is that it was his work and this is wonderful and this is what he needed to do and if somebody liked it that was great.”

Again we see Armand’s creativity in “Alone At Last.” Here he playfully reverses perspective by leading our eye downward rather than upward. He explains, “It’s about two little children who wander off in the town and out into the woods and are temporarily lost. It shows the voyage from the town at the top to way down at the bottom where they sit under a tree in a nice spot of sunlight, alone at last” (Zandstra Interview, 8-14-99).

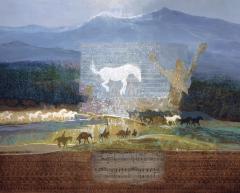

In the painting “Break Out,” one can see how Armand must have felt when he first heard Schnabel perform Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, subtitled “The Awakening of Powerful Feelings on Arriving in the Country.” In keeping with the first movement, Armand depicts dark horses climbing uphill while recurrent and interweaving patterns build a musical scaffold. As the climb reaches its crescendo, the horses pick up speed until at center stage a gravity-defying white horse takes a Lipizzaner leap into the air, throwing its rider into space. He and the rider are electrified, as though the symphony could carry them into a realm where musical notes light up into a galaxy of stars.

Well, down here you see, is the maze of monotony and repetition, automobiles, houses, every dog you see is on a leash. There's a dollar sign between every object, houses and cars, the mark of the dollar, which rules every damn thing. And then out of that comes the horse pack, the train of many horses leaving the scene. . . . and then there's the one leaping.

I changed the horse in dark to freedom in white. Now that's taken actually from a shot of a rodeo with a fellow that was just bucking for everything he's worth and the cowboy was leaving him. The cowboy had been thrown off. I did that for the intensity of the position. . . . There is a tension there. . . . That to me is the place to go. Yeah, here is my intention personified.