Before the semester ended in 1941 it was clear that he needed time to rethink. “I had to get a lot of things straightened out in my mind” (Dornbush/Zandstra Interview, 7-10-02) Traveling west to Cody, Wyoming, he found time enough to reorganize his thoughts in a landscape big enough and generous enough for him to envision what to paint.

His pocket change soon dwindled, particularly since he was unsuccessful in finding any employer sympathetic to his view of “keeping the Sabbath day holy.” From Cody he headed directly to New York hoping to find work in the art world. He initially stayed at the Sloan House YMCA and was filled with ideas to put to canvas. By then World War II had started. In the summer of 1942 he was hired by an ad agency under “false pretenses,” since they led him to believe he’d be working there as an artist. Instead, more errand boy than artist, he was frequently expected to step and fetch for top brass, shuttling guests to airports and running shirts to the laundry. He made a pittance of twenty-one dollars a week. By November of that year he left after a confrontation with a boss he regarded as rude and unreasonable (Dornbush/Zandstra Interview, 7-10-02).

From there he found work in Wilmington, Delaware, in a navy shipyard, as a tacker or spot welder on the hulls of ships. Due to the cold rainy weather, work was sporadic. Pay was poor. He wasn’t eating well, and although by then he seemed to have outgrown his seizure disorder, he was frequently ill with other maladies: nose bleeds, an infection in his jaw, colds, fever. Alone, as Christmas came and went, he wrote to his father from the YMCA a long despairing letter.

Dec. 29 Wilmington, Del.

Dear Dad!

This is your son writing again. He’s now come to a period of his life where he’s sincerely confused. This is only intensified by the fact that he’s made big errors. Errors which were in the form of disillusionment – stretched over a period of years. He’s consistently sought to get the Ideal down –– with the faith that the world wants it –– and him. He’s now, after much sad experience, found out at last that the world seeks after the ideal –– but not him who creates it. He’s found out the one unbearable, fundamental lesson, – namely that to be unique, to be a great artist, to assert individualism –– spells loneliness, loneliness.

Until fairly recently he’s kept the belief that he can be a great artist, and at the same time live a normal life –– to love and be loved. Well, there have been a very few of these ideal situations–– but they seem contrary to certain ironical rules of humanity. Your younger son is now only filled with regret, regret. ––– Why? Because he wasn’t more humble when young – because he didn’t go along with the rest of young people through school, college etc. And first of all arrange something most intelligent, yet practical. Instead he had a huge inferiority complex to overcome.

It all started with the period of epilepsy. This alone has put a fundamental curse upon him which he’s striven to build up against, compensate for, by means of art –– because it’s unique and helps a person’s morale. He’s done well in it indeed. But underneath this all he’s most human, he wants to love and be loved ––– he believes in Jesus Christ (Merizon Letters, 12-29-42).

Defeated and desperately ill, he was hospitalized in January, 1943, with pneumonia. Upon discharge, dreading to face more work in the harsh winter, he made plans to go to Phoenix, to a warmer safer climate where he could recover his health and paint.

Once again his plans were changed. Letters of March, 1943, indicate he had joined the U.S. Air Corps within weeks after Stalin had launched a major offensive against Hitler in Eastern Europe. All of this was alarming news: the threat of Hitler on the one hand, the threat of Stalin and the spread of Communism on the other, only to be rivaled by the threat of the Japanese in the Pacific. Fiercely patriotic, Armand had enlisted in the Army, expecting to fight the Japanese and not to return alive.

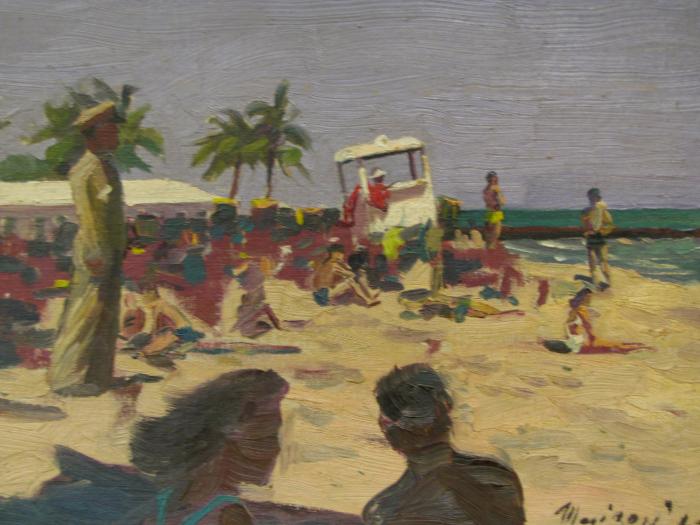

As a soldier he was assigned to Fort Custer in Michigan and then south to Miami Beach. Before long, illness struck again and he was hospitalized with the German measles. After recovering he returned to gas mask drills, rifle and Tommy gun (Thompson machine gun) practice, and more lectures on how to survive jungle warfare. In what spare time he had, he painted palm trees and army life, filling one sketch book after another.